I’ve been reading a chapter out of “The Sky is Your Laboratory, Advanced Astronomy Projects for Amateurs” by Robert Buchheim (Springer) regarding meteor studies. I’ve never tried recording observations of meteor showers before and was very thankful to have an introduction explaining meteors and how to observe and record your observations. I’ve elected to do the “Project A” which is just a visual count of a major meteor shower. In this case, Perseids.

My first question was how does a person make the distinction between a Perseid and any other meteor? The author describes…

The “radiant” of a meteor stream is the point in the sky from which all of the meteors appear to have originated.

So in other words, Perseids radiate from Perseus.

But what if some of the meteors look like they radiate from Perseus but are actually from a different shower? The magnitudes and velocity and length are a few ways to tell if they belong to the same shower you’re recording.

As a rough rule of thumb, a meteor’s path will be roughly half as long as its distance from the radiant.

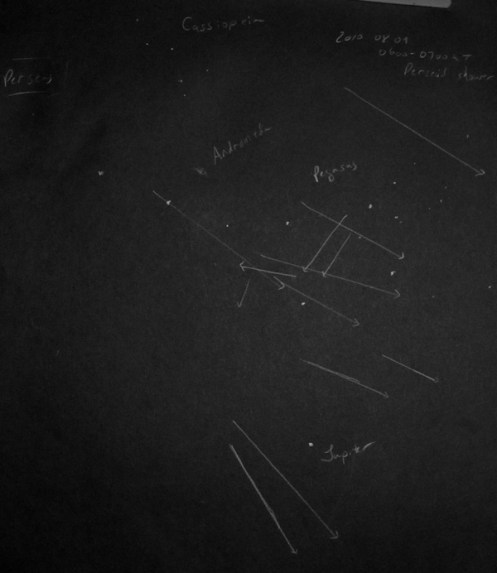

With that in mind, I decided to try sketching the meteors on a star chart, which really should have been gnominic charts. A fellow member of Cloudy Nights, GlennLeDrew, gave me the link to such charts: Charts designed just for meteor plotting.

Here’s what I came up with:

2010 August 10, 0600 UT - 0700 UT, 45 minutes observing time

The next step for me, which I’ve done tonight, is an hour’s worth of actual recording, broken down into 15 minute intervals, as suggested for this project in the book.

It would have been nice to continue on through the morning making several hours of observations. Not only was the weather not cooperating tonight, but I knew that I’d never be able to complete another hour of restful observation without falling asleep again while laying on my back in the comforts of my sleeping bag and all the night noises of nature. I believe the only thing that really kept me awake tonight was the smell of decomposing cabbage in the garden right night next to me from all the slugs having a late night supper each night.

Another CN member, Jane Houston Jones, posted very helpful insight on a similar project to mine. She’s taking it a few steps further with recording the magnitudes as well as identifying the sporadics and which showers (if any) they originate from. I will tackle that next. Thread on CN

Something else to take into consideration is how high the radiant is in the sky. When I started my observation tonight, Perseus’ tip was just starting to gain altitude from behind the trees. I could see the Double Cluster and then as far down as Mirtak. There were also trees to either side of my view, so that blocked out about 60% of my section of skies from Perseus. Add a few clouds and that might as well make it 70-80% blocked from any possible meteors radiating from Perseus.

For example: If Perseus was at zenith, the number of Perseids were 60 per hour, and there were no clouds in the sky and no obstructions with perfect conditions, you could ultimately view almost 100% of meteors from this shower (~ one Perseid meteor per minute) assuming you could catch them all. If Perseus is at the horizon, the number of Perseids you could potentially see under the same conditions drops to half that (~ one Perseid meteor every two minutes or 30 per hour). Add tree obstructions on either side blocking 25% of your sky makes it ~ 22.5 Perseids per hour. Add 30% cloud coverage and it drops the possible Perseids you might see to ~15.75 per hour. This amount decreases again for light pollution (take NELM into consideration), tiredness, interruptions, discomfort…..you get the drift.

As the radiant got higher, I started spotting a few meteors radiating outward to the SW. Unfortunately, the cloud coverage was becoming worse as Perseus gained altitude, which reflects in the record from tonight’s observation.

For more information on meteors and recording them, please visit The American Meteor Society and International Meteor Organization. It would make a fantastic project for you, your friends, and children.

Posted in Meteor Showers

Tags: meteors, Perseids